|

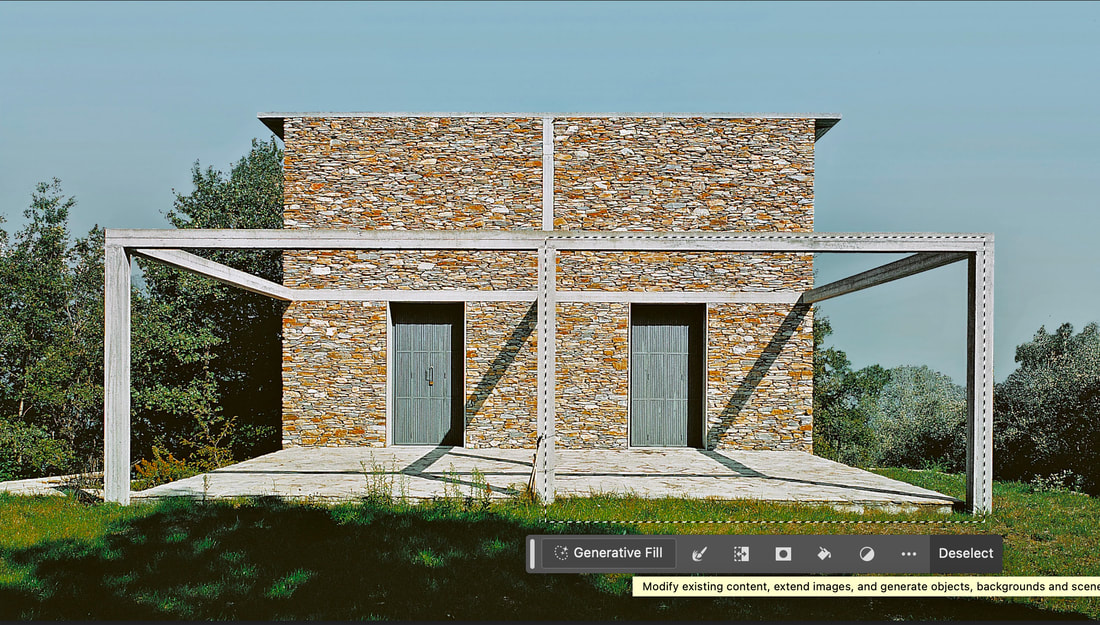

As an Adobe Creative Cloud user I’ve been very impressed with the new Generative Fill tool within Photoshop. The tool allows you to select an area of your image and remove items with a patched background generated. It also allows you to add items to images and looks to put them in in the correct scale and perspective. I guess that this is an AI tool and AI as a topic seems to have blown up over the last couple of months. As an architect and artist constantly trying to put together photomontages of buildings and artworks in their context, this tool seems incredibly useful. Gone could be the days of removing left over construction items from photos of finished buildings, adding people to mockups of concept designs of buildings or artworks. Even shade seems to be matched in and you can type in quite detailed descriptions of what you are looking for such as ‘people having a summer picnic’. Here is a base image of Herzog and De Meuron’s ‘Stone House’… … and then with ‘people having a summer picnic’ added to one side and then the other. Oddly there are different choices of people with the same search term but different parts of the outdoor space selected, the left and then the right. The faces of the people are also blurred a bit and I have a floating leg on one. About the tool, Adobe say: "Generative Fill—part of the revolutionary and magical new suite of Firefly-powered, generative AI capabilities—is grounded in your innate creativity, enabling you to add, expand, or remove content from your images non-destructively using simple text prompts in over 100 languages. Use this feature to automatically match the perspective, lighting, and style of your image, make previously tedious tasks fun, and achieve realistic results that will surprise, delight, and astound you in seconds. The new content is created in a Generative layer, enabling you to exhaust a myriad of creative possibilities and to reverse the effects when you want, without impacting your original image. Then, you can use the power and precision of Photoshop to take your image to the next level, surpassing even your own expectations." Thankfully, this tool is designed to help image editors rather that replace the creator. But I thought I’d see whether the Generate Fill tool would design an extension for me. I got these three variations for ‘house extension’, selecting the right side of the outside space. I then got something lightweight when asking for ‘glassy house extension’. I then selected the whole right hand side off the building space beyond and got a few other variations for extensions... There are some pretty interesting and impressive results. Some slightly odd things happen with the perspective of elements in you look at the colonnade parts. But there are some interesting design 'thoughts' from the AI tool such as windows aligning with the external wall above.

The tool will continue to improve, I don't believe/hope that AI cannot be used to generate design and take into account all of the information we use such as sun paths, internal room sizes, adjacent views and properties, etc, etc. However, it is certainly a powerful image-making tool and could be worth using to create inspiration images and references for designers.

0 Comments

CREDIT: Amanda Moore I’ve been working freelance as a creative for almost 3 years now and some obvious pros and cons have become apparent:

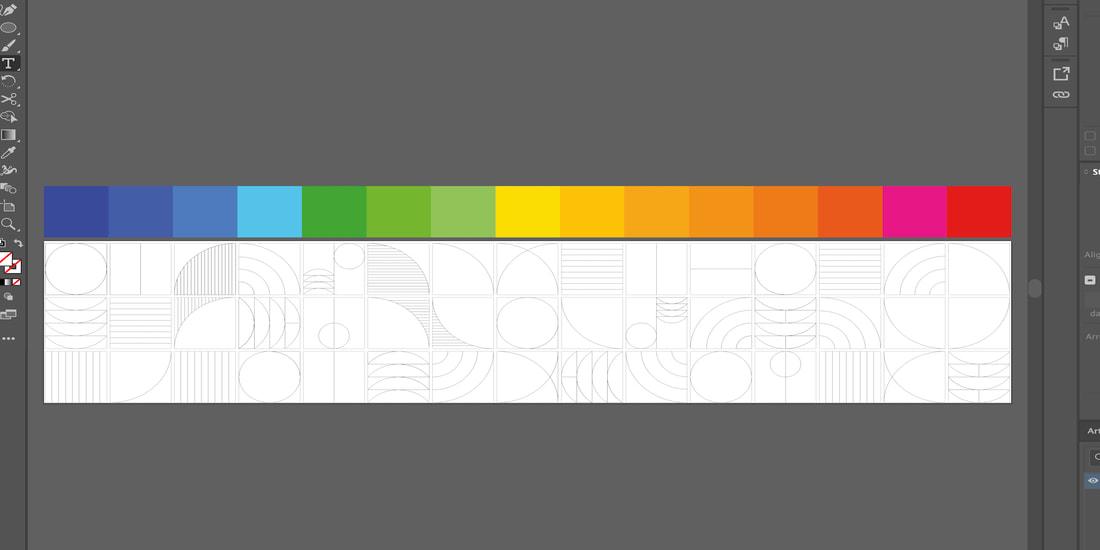

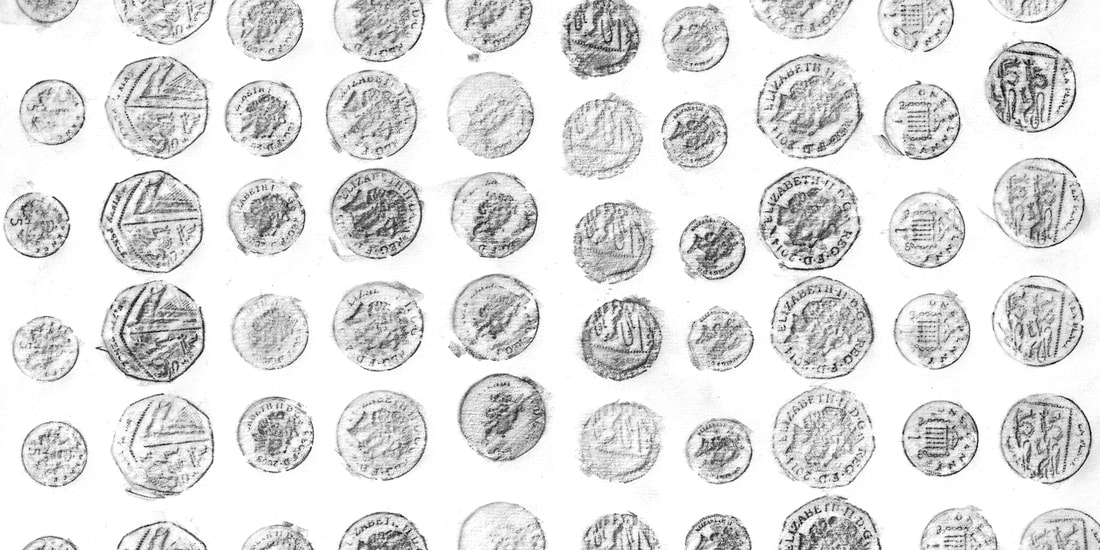

Pro: Making your own Decisions You can decide which projects to work on, when to programme them in and set up your own terms. You might have to take on projects you don’t want to in the beginning but then as you get a bigger client base you can start to choose. For example, if you’re an architect you might not want to design houses, or you might only want to design houses. You can also choose to work with nicer people, and people who pay on time. Con: Finding work You have to find your own work and schedule it in so that you have an even workload. Clients will sometimes hold on projects because of funding when you were banking on that project to pay your bills. You might be too busy at times if too much comes in at the same time. It might be best to start working a consistent number of days for your previous employer on a freelance basis, adding in the one-off projects on top. As an artist you may have to apply for 10 times the number of competitions you want to win and you have to remember if not selected that your work isn’t bad, they were just looking for something different. Pro: Making your own Routine No 9-5 may be the main reason people want to work freelance. You can take your kid out on a Monday and work on a Sunday, you can eat your lunch when you want, you can fit your hobbies in, and chores. You can work where you want, if your kid is sick you can have them at home with you. Con: Having no Routine You need discipline and a calendar to get your tasks done which is hard. You will need to impose a routine. I like to start with an hour of my hobby first thing before my kid is up so that each day starts with some kind of routine. Meetings can be all over the place, and people will think that you are sitting in an office all day and cancel a meeting about to start online when you’ve geared your whole day around it and you could have done something else. Pro: Becoming Entrepreneurial You will be more self-sufficient because you will have multiple clients and hence income streams. You will look out for opportunities but you have to stay in contact with people to hear about them. Con: Loneliness No work friends, no work friends, no work friends. I used to hate being in an open plan office, (25 people asking you every Monday whether you had a nice weekend), but no contact can be depressing, even during COVID times there were a lot of online meetings. You could do some work in a work hub with others in similar fields to have some contact, or work for a client in their office once a week for contact. Listening to podcasts while working or having a lunch break out can help if you work at home. Pro: No cap to your earnings If you work harder you make more money, in theory, rather than working harder hoping someone will give you more of the money they are making. Con: No guaranteed earnings - or benefits. You will need a reasonable emergency fund, ie, an amount of money you can live off until you can find a job if needed which may be 3-6 months. You will need to pay your tax, national insurance, set up a pension or long-term savings. You will need to take care of your own sick pay, holiday pay, software costs, training and a decent chair to sit in. Don’t use a wonky IKEA stool. Calculate a day rate of your previous gross PAYE salary x 30% to cover other benefits like pension, then divide by 220 days. CREDIT: Amanda Moore I spend a lot of time mocking up artist impressions of projects I’m working on. I’m no good at photorealistic images and so a filter which makes them look more like hand sketches saves me the time creating a hand sketch and also doesn’t look like an early 2000s computer game still. The most useful Adobe Photoshop filter I’ve found is the ‘find edges’ one which creates a version of an image which looks like a pencil sketch. When desaturated and overlaid onto the original image, it creates a kind of watercolour effect. Here is an example of an image I did for a commission during the Covid lockdown era for People United. I designed a floor mural which could demarcate social distancing in lockdown times, and in non-lockdown times it would make a public space more interactive. You can see the difference before and after using the filter: CREDIT: Amanda Moore I created the image using a photo of the place and adding in people and the design. I then saved a copy of the layered Photoshop file and flattened the layers. I went to Filter > Find Edges to create the line drawing. I then used Mode > Grayscale to remove the colour, although you could also use the Hue/Saturation settings to just reduce the colouring. CREDIT: Amanda Moore I then copied and pasted this layer onto the original file as the top layer and played with the transparency levels. You may need to cut out bits in places using the wand selection tool if the white background is too much.

The other thing which you could add to de-realise the image further is a watercolour layer. You can find a watercolour image online and copy and paste it into your image file. Desaturate it and then reduce the transparency to around 10% or below and this adds a mottled texture. This filter has allowed me to produce many last-minute artist impressions. CREDIT: Richard Chivers. Gosport Mural, Amanda Moore 2022 Over the last two years I’ve been creating more public artwork using vinyl printing rather than hand paint or applying art traditionally. The process goes like this…design an artwork which is site-specific for the client, (usually local authority), approach a vinyl printing company to survey the site accurately and quote for the work, have them print and install the final work like outdoor wallpaper. I’ve used adhesive wraps for three types of installation:

The advantage of using a vinyl printing subcontractor is speed. I tend to mock up artwork using Adobe Illustrator mostly using vector-based lines and shapes which cuts out concerns over image resolution. I then approach a subcontractor I’ve worked with previously and ask them to measure on site and quote for the work, plus provide a method statement detailing how they will install safely and any product warranties. I’ll often have a sample installed on the site so that we can see how the material will stretch over textures such as brickwork and how easily it is removed. CREDIT: Amanda Moore. Testing vinyl wrap. The project I worked on in collaboration with Studio BAD in Gosport in 2022 involved designing a wrap for a snooker hall building as part of a trail of new art within the town centre. I designed a mural which picked up on Goport’s naval heritage by taking dazzle boat painting patterns and combined this with colours and motifs seen on heritage buildings around the town. All of this was drawn in Adobe Illustrator and sent to Mac Signs based in Southampton who installed the work using a scaffold tower within a week, although this week of labour was spread out around poor weather. CREDIT: Amanda Moore. Eastleigh translucent vinyls In Eastleigh I designed a large set of translucent vinyls which were based on Art Deco patterns seen on an early twentieth century building in the town. These were installed to glazed colonnades and create reflections onto the ground. The prints were cut around the unevenly spaced mullions on site rather than needing to measure each piece of glass. The works were installed to the underside around the town, bird poop not landing on top. CREDIT: Richard Chivers. Southampton Guildhall urban rug. For Southampton’s Guildhall Square an urban rug was formed using coloured squares made from recyclable aluminium. These squares were arranged as pixels forming architectural motifs on the Guildhall building. The texture for floor art is important in terms of guaranteed slip resistance in public areas. These didn’t quite hold up as well with the local skateboarders and they tore at the edges but it worked well as a temporary installation.

CREDIT: Alamy Stock Photo, Office Space 1999 Whilst working in the construction industry as an architect, I always had an additional side-income as a freelance artist. This meant that I had the comfort of a full-time income whilst gaining experience in applying for freelance commissions, winning them, carrying out the work independently and doing my own billing and accounts. My freelance work meant that there was no cap on my overall salary as I could earn extra income freelancing.

But how do you know whether it is a good idea to quite the 9-to-5 and go fully freelance? My main reasons were:

But when do you know that you are ready to go freelance full-time? For me it was when:

And some of the steps I took were:

Since working freelance the benefits have outweighed any negatives. For many people, (those inputting information into a computer whether it be words, numbers or 3D information), work can be done flexibly and from home or a small office/studio. I’ve experienced a range of lifestyle changes since working from home:

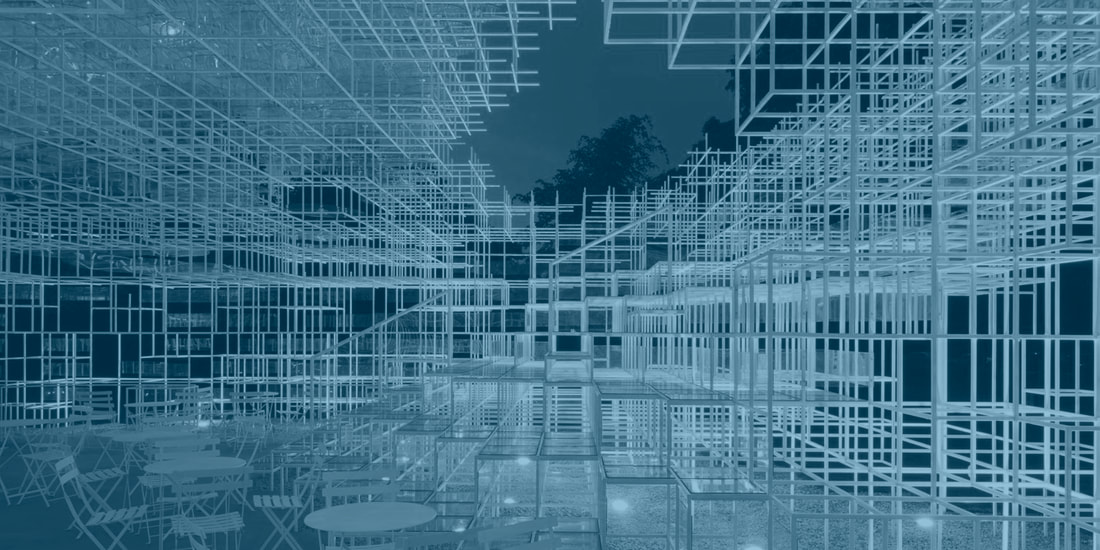

Overall I would say that if you want more flexibility in life or other improved conditions, you may want to chat to your employer first. However, if there is no movement or compromise, you may want to try freelance work - as long as you’ve built up a safety net. I never want to go back... CREDIT: Collage: Amanda Moore, Serpentine Pavilion 2013, Sou Fujimoto Buildings are permanent right? A naive friend once asked me whether architects would always have work because ‘they must have built all the buildings by now’. I studied architecture after studying fine arts in order to be involved in physical projects which would be more permanent than fine art, in terms of their longevity and relevance. Surely they would therefore also be more important and impactful? Art seemed to be more transient based on trends and what was popular for collectors and galleries. But is architecture and building design permanent? Should it be? Most clients expect at least 150 years of useful life from a building which is costing them several millions to construct. We raise floor levels above flood levels, with allowances for climate change, and carry out copious coordination exercises with materials and system providers. Maybe buildings can last at least this long and this length of time can be considered ‘permanent’. Victorian residential properties are popular in the UK and are well looked after by each generation of custodian. But should many non-residential buildings, such as commercial buildings, public buildings and temporary accommodation, be permanent? A commercial building designed with enough solidity, and embodied carbon, to last hundreds of years may not be wanted after forty. If building uses often change, perhaps the structural frame should always be designed to be flexible and reusable. This might be easier to achieve with traditional building technologies such as steel or concrete frame, but not for more sustainable technologies such as cross-laminated timber which may not allow flexibility in glazing or internal wall positions. There has been an obvious trend for temporary architecture in recent years including pop-up retail, outdoor event spaces and urban parklets. This feels to have grown during 2020 with a need to utilise more outdoor spaces due to reduced permitted indoor occupancy during the pandemic. Temporary architecture allows the proposed use of a place to be introduced and tested by communities before more expensive built interventions, and accepts flexibility and community input. It can also be free to be of its time, trendy in colour or form. It doesn’t have to be timeless. Maybe the design life of 'temporary architecture' can be extended from the length of a single event to the length of a tenure. CREDIT: Photo: Dinesh Mehta, Kumbh Mehla Festival set up with temporary walls and floors Can humans expect any of our interventions to be permanent?Is this wishful thinking as a kind of immortal legacy? When I worked for a large practice in London, the partners were always excited by projects which involved masterplanning where a developer had procured several plots of land as new street networks and proposed uses could be developed which they felt would likely have greater longevity than the individual buildings. Aside from building use, building standards often change and old buildings may not be able to be upgraded to ‘current’ standards. Questionable quality is another issue which can counteract the designed mass and solidity of buildings. There are unfortunately many instances where architect-designed buildings are not weathered well and it’s a (short) matter of time before they decay when all the mastic fails. This often seems to come down to confusion between the role of the architect and the contractor and who will take responsibility for the final detailing. And so is architecture more or less permanent than art?Artworks may be protected for millennia if they constitute an important financial or cultural commodity. Public art could also potentially have a longer life span than a building. A public art project I was fortunate to work on, Black Down Stone Circle, Dorset, was installed in 2016. It consists of five totems produced from local Forest Marble stone. The totems align with true north and the summer and winter solstice sunrise and sunset positions specific to the site. Sunlight passes through openings in the totems and hits a central Portland standing stone. The project was built by a skilled stone mason called Tom Trouton and the alignment was advised by specialist Simon Banton. It is now used as a ceremonial site by spiritual groups on the solstices. CREDIT: Photo: Simon Banton, Black Down Stone Circle Contrary to my expectations at the beginning of my architectural studies, a built project like this may prove to have more permanence than most architectural projects I've worked on in terms of physically being there and being relevant. The sculpture is robust and well-built by a craftsperson rather than relying on the integrity of foil tapes and membranes. The artistic idea does not age or need to be updated in line with any style or technical standards.

These days it seems more appropriate to me that art can have permanence but architecture should be more temporary. CREDIT: Photo taken at Bedford Place, Southampton, of artist decorated road closure blockades, but what now happens behind?: Amanda Moore Since the pandemic started early this year, people have been forced to become more ‘local’. Working from home, (which I’ve now been doing for 9 months), no distant holidays, less inessential travel. Strangely, there have been some potential upsides to this new way of living which could point the path to a more permanent way of simplifying our lives and making us more rooted in our local environment, for the better. For myself, being housebound has made me more appreciative of my home and garden space and forced me to look at ways of optimising small areas of space. I’ve created a reading nook in the hallway and densified storage, as a posed to thinking about extending or buying a bigger home. I’ve gotten to know my neighbours better, we’ve set up benches in our driveways and had lunchtime coffees. I’ve cycled around during the one hour of government-approved daily exercise to scope out parks and woodland cycle routes I didn’t know about and people seemed to make more eye contact and smile more that usual during the summer, enjoying any level of human contact. Within town centres, some roads were closed in order to allow shops and cafes the opportunity to spread out into the streets due to restrictions on internal occupancy. In my own town, the two main Victorian streets have been closed since July which has not only removed the traffic, but also the linear barricades formed from parked cars which prevented people moving from one side of the street to the other in a more organic way. Both streets are served by back alleyways in any case and there is nearby accessible parking. The last few months of reduced car access has likely had little effect on trade, more the ‘inessential trade’ restrictions or general increase in online shopping pre-COVID. However, the streets have had an eerie silence where the white and yellow road markings remain and people are still not used to waking down the middle of the streets. This is an opportunity though, to rethink whether cars should be allowed into every street of our small town centres, making way for people to have a slower and more friendly retail experience, meandering down streets rather than driving to a shop and leaving, or driving out of town to bigger malls and hyper markets. Using the streets between shops as pop-up markets, weaving a garden through the town, having additional seating or events spaces sits in line with a retail ‘experience’ which has more physical interaction and connection with our local towns, and ties in with encouraging less car use and carbon reduction. CREDIT: Photo, Romsey Parklet: Mill Road Summer Architects, designers and planners should be starting with the smaller traditions and rituals of each community such as yearly events, or seeking out local makers and performers who could benefit from having a public platform. Asking people what they want and making temporary and flexible interventions in line with those potential users, introducing a new use for road and parking spaces so that people can see the benefits and feed in ideas. A bottom-up approach rather than a top-down one which usually involves building large permanent interventions without ensuring that people are actually going to use them.

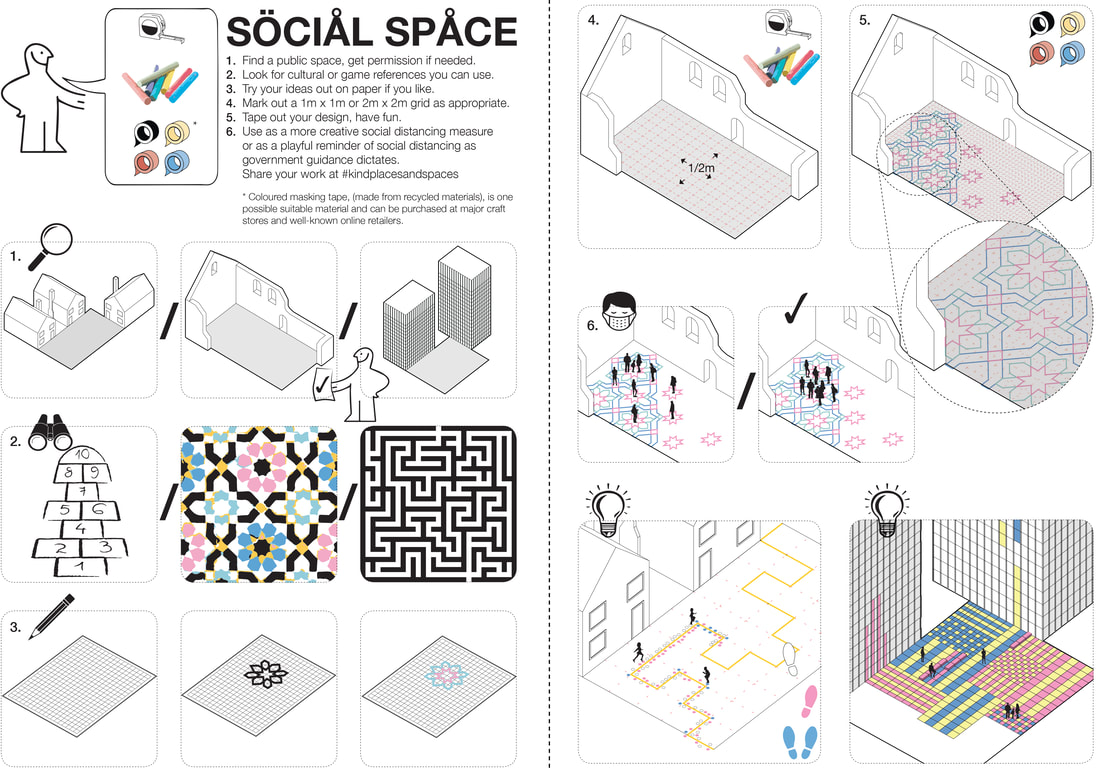

I currently have the opportunity of working with teams on a couple of these town centre projects, walking the streets and talking to local traders and groups about how to make the space around their business or studio more of a transitionary zone, ie; a parklet in front of a restaurant, a selling space in front of a workshop, a market stall for traders who sell in several towns, an activity or event space for local school or theatre groups ... all of this making the market street potentially more of an experience which draws people in as an alternative to online or out of town shopping... Go [or stay] local. CREDIT: Image: Amanda Moore, SÖCIÅL SPÅCE Project 2020 When lockdown started in early 2020, in relation to the global pandemic, the arts were badly affected. In terms of galleries, many had been forced to temporarily close in towns due to social distancing measures. In the summer I was lucky to be commissioned by People United, along with 5 other artists, to design artistic concepts which would make social spaces kinder and, well, more social. This culminated in a graphic leaflet which people could download at home. The idea was for communities to work together to produce an outdoor artwork which would assist with social distancing in a playful way. The artworks would allow us to interact more with our local public realm, particularly at a time when indoor spaces were subject to tighter occupancy guidelines.

Through 2020 and beyond, could there be a greater impetus to take artwork outside onto the streets and what are the benefits?

And are there any limits to the placement of art outside of the gallery?

These projects are often commercially sponsored, paid for by arts councils and trusts or form part of planning application agreements or council regeneration projects. They can be temporary or permanent and they can have a much larger role than art as commodity. They are art as identity, interaction and engagement of people with their surroundings. CREDIT: Drawing: Amanda Moore When working as a freelance artist or creative, you need to be clear with your client about fees for your services and any other costs from the outset. You can also lose out on hard-earned fees because of simple invoicing mistakes. I definitely have. Here are some helpful tips: Decide whether you are charging an hourly/day rate, or flat feeIf the project is a service, like designing some graphics or editing photos as part of an ongoing freelance gig, you may wish to invoice on an hourly or daily rate. Make sure that you agree a rate in advance. It may be worth joining an artist membership site like a-n, (a-n.co.uk), for current recommended day rates. If your project is a one-off larger commission such as a piece of bespoke artwork, you may be better off agreeing a flat fee. Work out a budget breakdown to include estimated time you'll need for; project research, meetings, site visits and production using your day rate. Include an estimate of any necessary expenses and fabrication costs. Get quotations from any external fabricators. Day rate invoicingIf you are working on a day rate, include the time worked on the invoice and your hourly/daily rate so that there is no confusion over this. If extra work is required later, you can easily separate the extra work from the work already completed and invoiced for. Flat fee invoicingAgree a payment schedule if the work will run over a longer timeframe. This may be based on completion of certain tasks or on set dates along the way such as once per month over a six month project. This is very important. Otherwise you could end up working for a long time with no payment which will affect your cash flow. You may also end up invoicing periodically based on the amount of time you have spent and not end up receiving the full lump sum fee agreed once the project is complete. If you have to outlay a lot of money on materials, make sure that your payment schedule is timed and sufficient to cover these costs to reduce your risk. Scope of servicesMake sure to detail what you will be responsible for and what will be provided by others before starting any work. Who is printing the final artwork? Will you be expected to pay for any consultant costs such as engineering fees for a bespoke three-dimensional work? How many meetings will you be expected to attend? How many design revisions will you allow within the agreed fee? This all needs to be agreed or your fee could be spread very thinly. Delivery and installationFollowing on from the point above, make sure that you agree with your client who will be hanging or installing any physical work and whether you are expected to arrange delivery. Get quotations from specialist companies as there could be a massive cost difference between a small van delivery and a large truck with crane. ReceiptsKeep your expense receipts as proof of costs for clients if required. You will also need them in order to claim any tax back on your yearly income tax return. Basic invoice information to include:

Tax on incomeKeep copies of invoices in separate folders for each tax year with receipts. This will make completing your income tax return much easier. Register to pay tax in your country, (called Self-Assessment in the UK), and make sure to put the tax away in a separate account when you get paid so that you don't spend it! Don't forget that there may be other deductions such as student loan payments and National Insurance in the UK.

CREDIT: Photo (and mess): Amanda Moore You may be planning to join a visual arts programme as an undergrad with a broader base. Or you might be about to specialise as a grad student in painting, sculpture, film, print, illustration or photography. How do you make the most of this exciting opportunity? 1. Choose a school which has the right teaching style for youCourses vary widely. Some people will be happy to be shown to their studio space and left there for 2 weeks until the next tutorial. Others will prefer a more structured course. The school I attended had art history lectures, life and anatomical drawing classes and technical workshops which worked better for me when transitioning straight from high school/college. With less structured courses, you will likely have to be more proactive in reading, researching and visiting shows. Something inspirational has to go in for something creative to come out. 2. “Don’t borrow, steal”This was a great piece of advice given by a tutor. It will be tempting to try and emulate the style of an artist you like. The better approach is to understand what their work is about, what is the concept, and then own that, improve on it and make it yours. Start with the idea and the style will follow. 3. Make your art politicalYour art doesn’t have to be overtly about topical political issues but it’s easier to build up a portfolio of work if there is a central theme or reason for why you are making it and showing it to others. Art is also a great platform for expressing or critiquing something, even for critiquing art itself. So many ideas are communicated on social media platforms to people who already have similar views and so exhibiting art is an opportunity to bring ideas to a wider network. 4. Critique is not criticismCrit days can feel like a firing squad as you clear up your studio space and prepare to stand up and explain your work to tutors, visiting lecturers and your fellow students. A well-run crit should give objective feedback and help you to feel clearer in the direction your work is going. For better outcomes, choose elements of your practice which you feel you require feedback on and ask another student to take some notes for you as we all have a tendency to only remember the negative comments. 5. Market your artBe proactive and don’t rely solely on the final degree show for people to see your work. Tutors may not offer any guidance on this. You might use social media platforms to showcase your work whilst also giving more insight into your unique concepts and making techniques. Setting up a website will enable you to direct people to your work when you meet them. Set up your own show, or a themed group show, and be open-minded about venue locations with good footfall. Apply for commissions and competitions. 6. Grow your networkFollowing on from point 5., talk to people, lots of people. Talk to your studio colleagues about goals, share contacts, offer to help each other. If you meet someone and collect their card ‘old-skool’ or connect with them on social media, set up reminders to check in with them now and again. Share something of interest or find out whether you can help with something they are working on with no expectations in return. Not all opportunities will come your way by applying for them, many will be created and offered from within your network. 7. Take advantage of other school resourcesYour school may have a whole set of wider resources which you can use as part of your paid tuition. This may include specialist equipment, lectures in other subjects, business courses or even counselling. All of these resources would cost you some serious coin if you paid for them privately. 8. The art world can be a fickle placeIt will prove difficult to understand why curators and galleries prefer certain artworks and artists and some of your colleagues may be more sought after than you at the final degree show. Your art is not bad, there is a place or a situation for all art. It may not be this gallery but another one, it may be for publications, for public commissions, for private collectors, etc. 9. Find ways to make your practice affordable post-schoolIn school you may have access to everything from printmaking presses to welding equipment. However, you may or may not have easy or affordable access to these tools after school. Think about diversifying the materials you use so that you can keep creating without having to outlay a lot of money on equipment. Depending on your location, you can also rent workshop space on a daily basis. 10. You will always be an ArtistAs I approached graduation, I knew that I would need to take a day job and find a way to come back to producing my art in the future. If you want to, or have to, take a break from creating art full-time after graduation, don’t worry, you will always be an Artist. Firstly, make your art for yourself. You will also bring a way of seeing things into everything else you do and you may even become a different kind of creator - a writer, a musician, a marketer, a designer … be open to all opportunities. What are some of the most valuable things you have learned at art school?

|

AuthorWhat am I doing here? I'm collecting sea water to fill 1,000 bottles and hang them from a scaffold inside an old ruin. Why? Why not? Archives

December 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed