|

CREDIT: Collage: Amanda Moore, Serpentine Pavilion 2013, Sou Fujimoto Buildings are permanent right? A naive friend once asked me whether architects would always have work because ‘they must have built all the buildings by now’. I studied architecture after studying fine arts in order to be involved in physical projects which would be more permanent than fine art, in terms of their longevity and relevance. Surely they would therefore also be more important and impactful? Art seemed to be more transient based on trends and what was popular for collectors and galleries. But is architecture and building design permanent? Should it be? Most clients expect at least 150 years of useful life from a building which is costing them several millions to construct. We raise floor levels above flood levels, with allowances for climate change, and carry out copious coordination exercises with materials and system providers. Maybe buildings can last at least this long and this length of time can be considered ‘permanent’. Victorian residential properties are popular in the UK and are well looked after by each generation of custodian. But should many non-residential buildings, such as commercial buildings, public buildings and temporary accommodation, be permanent? A commercial building designed with enough solidity, and embodied carbon, to last hundreds of years may not be wanted after forty. If building uses often change, perhaps the structural frame should always be designed to be flexible and reusable. This might be easier to achieve with traditional building technologies such as steel or concrete frame, but not for more sustainable technologies such as cross-laminated timber which may not allow flexibility in glazing or internal wall positions. There has been an obvious trend for temporary architecture in recent years including pop-up retail, outdoor event spaces and urban parklets. This feels to have grown during 2020 with a need to utilise more outdoor spaces due to reduced permitted indoor occupancy during the pandemic. Temporary architecture allows the proposed use of a place to be introduced and tested by communities before more expensive built interventions, and accepts flexibility and community input. It can also be free to be of its time, trendy in colour or form. It doesn’t have to be timeless. Maybe the design life of 'temporary architecture' can be extended from the length of a single event to the length of a tenure. CREDIT: Photo: Dinesh Mehta, Kumbh Mehla Festival set up with temporary walls and floors Can humans expect any of our interventions to be permanent?Is this wishful thinking as a kind of immortal legacy? When I worked for a large practice in London, the partners were always excited by projects which involved masterplanning where a developer had procured several plots of land as new street networks and proposed uses could be developed which they felt would likely have greater longevity than the individual buildings. Aside from building use, building standards often change and old buildings may not be able to be upgraded to ‘current’ standards. Questionable quality is another issue which can counteract the designed mass and solidity of buildings. There are unfortunately many instances where architect-designed buildings are not weathered well and it’s a (short) matter of time before they decay when all the mastic fails. This often seems to come down to confusion between the role of the architect and the contractor and who will take responsibility for the final detailing. And so is architecture more or less permanent than art?Artworks may be protected for millennia if they constitute an important financial or cultural commodity. Public art could also potentially have a longer life span than a building. A public art project I was fortunate to work on, Black Down Stone Circle, Dorset, was installed in 2016. It consists of five totems produced from local Forest Marble stone. The totems align with true north and the summer and winter solstice sunrise and sunset positions specific to the site. Sunlight passes through openings in the totems and hits a central Portland standing stone. The project was built by a skilled stone mason called Tom Trouton and the alignment was advised by specialist Simon Banton. It is now used as a ceremonial site by spiritual groups on the solstices. CREDIT: Photo: Simon Banton, Black Down Stone Circle Contrary to my expectations at the beginning of my architectural studies, a built project like this may prove to have more permanence than most architectural projects I've worked on in terms of physically being there and being relevant. The sculpture is robust and well-built by a craftsperson rather than relying on the integrity of foil tapes and membranes. The artistic idea does not age or need to be updated in line with any style or technical standards.

These days it seems more appropriate to me that art can have permanence but architecture should be more temporary.

0 Comments

CREDIT: Photo taken at Bedford Place, Southampton, of artist decorated road closure blockades, but what now happens behind?: Amanda Moore Since the pandemic started early this year, people have been forced to become more ‘local’. Working from home, (which I’ve now been doing for 9 months), no distant holidays, less inessential travel. Strangely, there have been some potential upsides to this new way of living which could point the path to a more permanent way of simplifying our lives and making us more rooted in our local environment, for the better. For myself, being housebound has made me more appreciative of my home and garden space and forced me to look at ways of optimising small areas of space. I’ve created a reading nook in the hallway and densified storage, as a posed to thinking about extending or buying a bigger home. I’ve gotten to know my neighbours better, we’ve set up benches in our driveways and had lunchtime coffees. I’ve cycled around during the one hour of government-approved daily exercise to scope out parks and woodland cycle routes I didn’t know about and people seemed to make more eye contact and smile more that usual during the summer, enjoying any level of human contact. Within town centres, some roads were closed in order to allow shops and cafes the opportunity to spread out into the streets due to restrictions on internal occupancy. In my own town, the two main Victorian streets have been closed since July which has not only removed the traffic, but also the linear barricades formed from parked cars which prevented people moving from one side of the street to the other in a more organic way. Both streets are served by back alleyways in any case and there is nearby accessible parking. The last few months of reduced car access has likely had little effect on trade, more the ‘inessential trade’ restrictions or general increase in online shopping pre-COVID. However, the streets have had an eerie silence where the white and yellow road markings remain and people are still not used to waking down the middle of the streets. This is an opportunity though, to rethink whether cars should be allowed into every street of our small town centres, making way for people to have a slower and more friendly retail experience, meandering down streets rather than driving to a shop and leaving, or driving out of town to bigger malls and hyper markets. Using the streets between shops as pop-up markets, weaving a garden through the town, having additional seating or events spaces sits in line with a retail ‘experience’ which has more physical interaction and connection with our local towns, and ties in with encouraging less car use and carbon reduction. CREDIT: Photo, Romsey Parklet: Mill Road Summer Architects, designers and planners should be starting with the smaller traditions and rituals of each community such as yearly events, or seeking out local makers and performers who could benefit from having a public platform. Asking people what they want and making temporary and flexible interventions in line with those potential users, introducing a new use for road and parking spaces so that people can see the benefits and feed in ideas. A bottom-up approach rather than a top-down one which usually involves building large permanent interventions without ensuring that people are actually going to use them.

I currently have the opportunity of working with teams on a couple of these town centre projects, walking the streets and talking to local traders and groups about how to make the space around their business or studio more of a transitionary zone, ie; a parklet in front of a restaurant, a selling space in front of a workshop, a market stall for traders who sell in several towns, an activity or event space for local school or theatre groups ... all of this making the market street potentially more of an experience which draws people in as an alternative to online or out of town shopping... Go [or stay] local. CREDIT: Medical Drawing: Amanda Moore Which profitable jobs can you do with an art degree? Quite a lot, plus, you have the benefit of mixing and matching them for a more varied work-life than the average person usually has.

Here is an idea list of 60 potential jobs for artists including ones I've personally tried. Why 60? Because this was how many I could think of in one hour. I'll keep adding to this list:

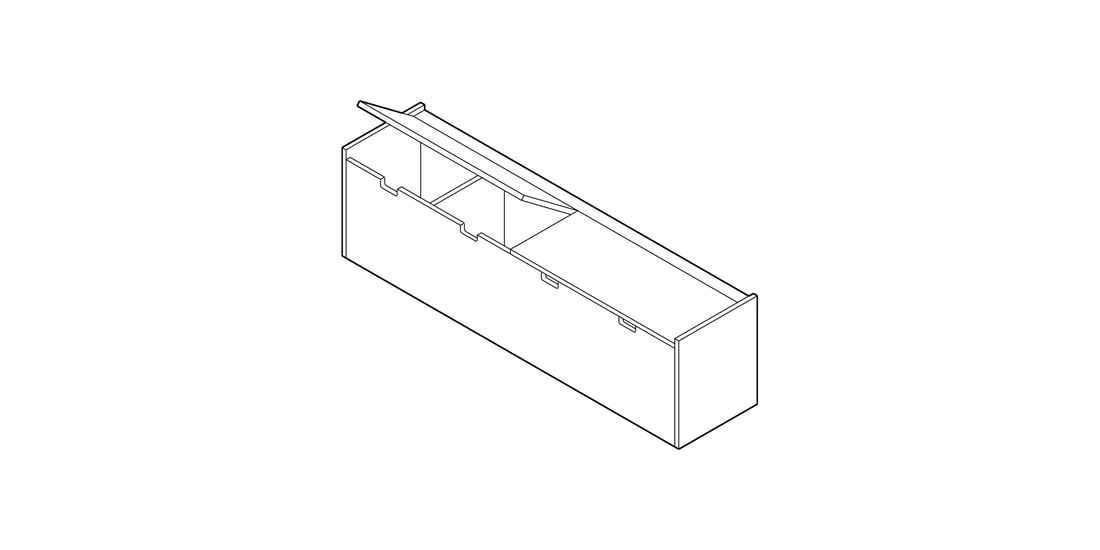

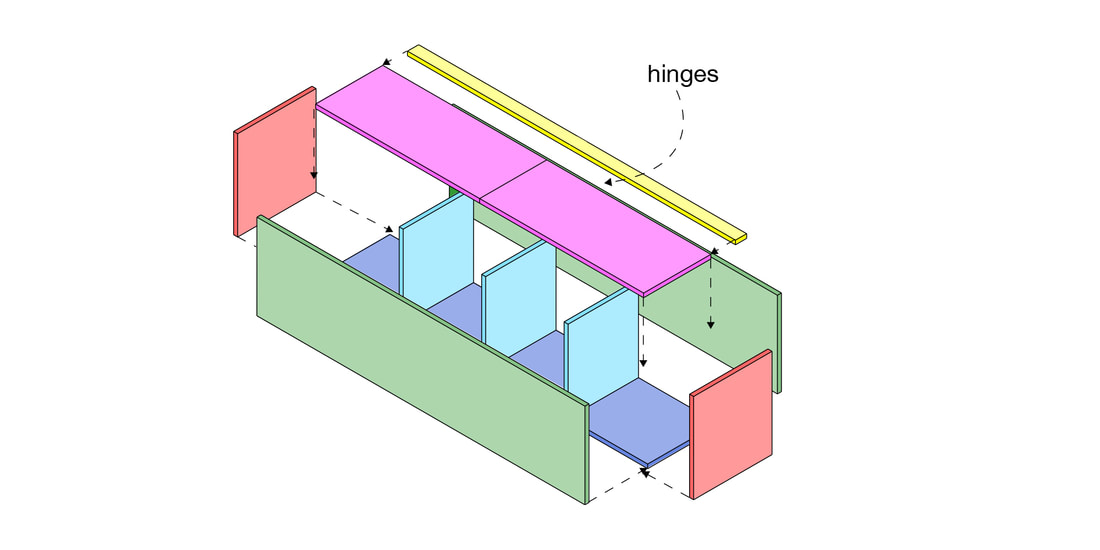

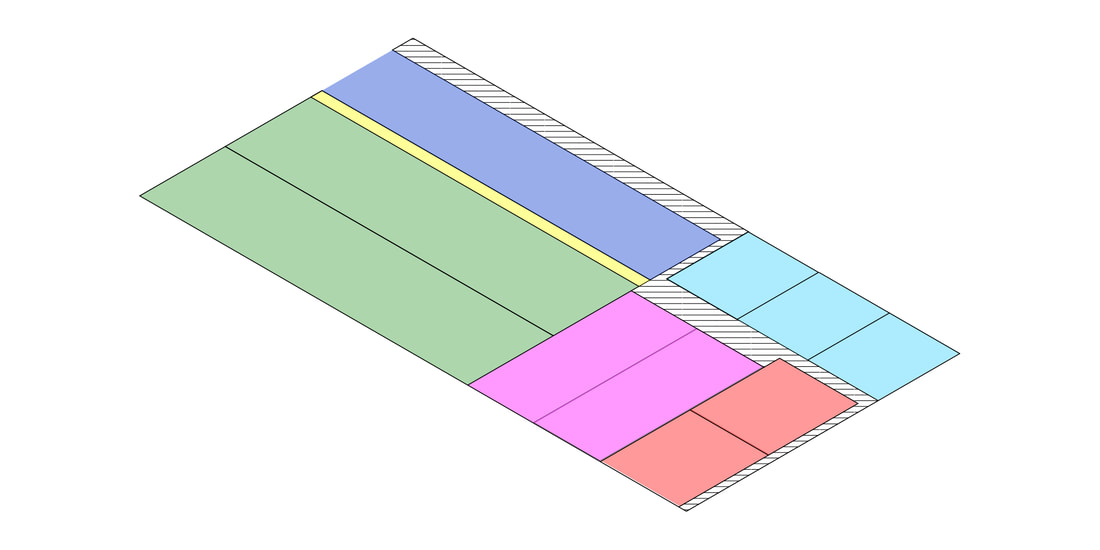

CREDIT: Photo: Amanda Moore In this 'Make Stuff by Hand’ series of posts I will share items built using minimal tools. Using your creativity to build things which can be used in your home is incredibly rewarding. However, watching YouTube videos by people with an entire workshop setup can be disheartening. What if all you've got is a drill and a saw? Here I outline the steps in making a plywood storage bench: 1. Measure your spaceThe instructions and cutting list included here will show the design for a 1.5m x 350mm bench to fit the space between two bookcases and create a seat under a window. You may need to adjust these dimensions to work with your particular space. 2. Choose your materialsSpruce plywood has been used for this project and can be purchased at a timber yard or popular DIY store. They should be able to cut it for you. The cutting list here is based on an 18mm material thickness. 3. Draw up your designNot everyone has 3D CAD software but you can download software like Sketchup for free, www.sketchup.com/plans-and-pricing/sketchup-free. You can model your item to scale and then take it apart and lay the pieces out into a cutting list. You want to try and lay out your pieces so that you require as few sheets of plywood as possible. Here I managed to get all of the pieces to fit onto one standard sheet of plywood: CREDIT: Drawings: Amanda Moore REMEMBER to allow for the saw blade thickness, so you will need a little wastage of material as allowed here. 4. Take your cutting list to a supplierChoose your material and try to get the least cr*ppy pieces. There is often one bad side with standard construction plywood and you could make this the bottom, back or inside. Sorry guys outside of the UK, I only do metric. CREDIT: Drawing: Amanda Moore 5. Choose either brackets or strip wood to make the jointsThis project used strip wood as it was cheaper. You could use small brackets though. You will also use wood glue to create stronger joints. Make sure that your wood screws are not too long, ie; less than the thickness of the panel material plus the strip wood or bracket thickness. I also used hand clamps to help hold things in place and used strip wood at most joints for strength. You can see the 'bad' side of the timber being situated inside the bench. 6. Hinges and openersYou can use individual hinges or continuous piano hinge which can be cut to size. I also decided to cut out four slots to allow you to open the lids. This involved drilling good-sized holes to create each curved corner and simply cutting with a saw and chiselling out. 7. FinishingLightly sand any sharp edges and varnish the bench to show off the natural wood grains. I chose to paint the interior of the bench in a chalk paint by Rustoleum, www.rustoleum.com/product-catalog/consumer-brands/chalked/. I also added restrictor hinges for child safety, and to stop the lids hitting the wall, plus sticky felt pads to the underside to allow the bench to be moved around without scuffing the floor. Finally I decided to sew two cushions from wool felt with wadding inside and fitted them with velcro, but this isn't necessary. Good Luck!

CREDIT: Photo: Amanda Moore What is a crit?An architecture ‘crit’ or critique is an opportunity to present your project to a wider audience, a panel made up of tutors, professional architects and also your peers. What is it for?A crit is often not a formal part of the grading process although it may give an indication of where your project currently sits in terms of assessment. A crit should provide an opportunity to have a discussion with a wider circle of people than your tutors and receive feedback to help you develop your project further. Here are some tips in preparing for your architecture crit: Pin up a page for each part of your design conceptEach part of your idea such as site analysis, research related to the brief, orientation of the building, materials, and massing should have at least one sheet on the wall dedicated to it. Work smartDon’t spend time doing dozens of sections or dozens of plans. Make sure that each part of your idea is represented as above. If you are short on time, use your model by lighting it and photographing it from different internal and external viewpoints. Keep your presentation conciseEvery project doesn’t need a long starting analysis of where the sun rises and sets. Everyone already knows that and it is a given that the building would be designed with this in mind. Filter your work and pull out the more poignant aspects of the site and project. You could even include a sheet on the wall with a list of the main bullet points about your project. Don’t read out your presentationIf there is a clear order to your sheets you should shouldn’t need to read out information. You know your project better than anyone else and the sheets should help provide cues. Don’t worry about negative feedbackThis is a hard one. The crit isn’t necessarily part of the grading process. It should be there to provide objective feedback to help you improve your project. Try to not take it personally and attend the whole day so that you can compare your feedback to that of your peers. Think about the main things you want to get from the critYou may have questions you’ve been asking yourself about your project in the run-up. Write them down in your notebook and use the crit as a chance to discuss with the panel. Practice your presentationDo a run-through to time your presentation and use a friend or family member who isn’t an architect. The presentation should be clear enough that a non-architect can understand what you’re talking about. Ask a friend to take notesIt can be hard to remember references and other information given by members of the crit panel when you are presenting. You may also remember more of the negative comments than positive ones. Act professionallyDressing relatively smartly and addressing the crit panel goes a long way. Don’t treat them as if they were a firing squad. Move around and take them through drawings and models. Also, start your presentation by telling them what your project is and the site location before going into the ‘journey’. Get some sleepWorking until 3am and turning up unwashed and drowsy is going to distract from your work and result in a poor verbal presentation.

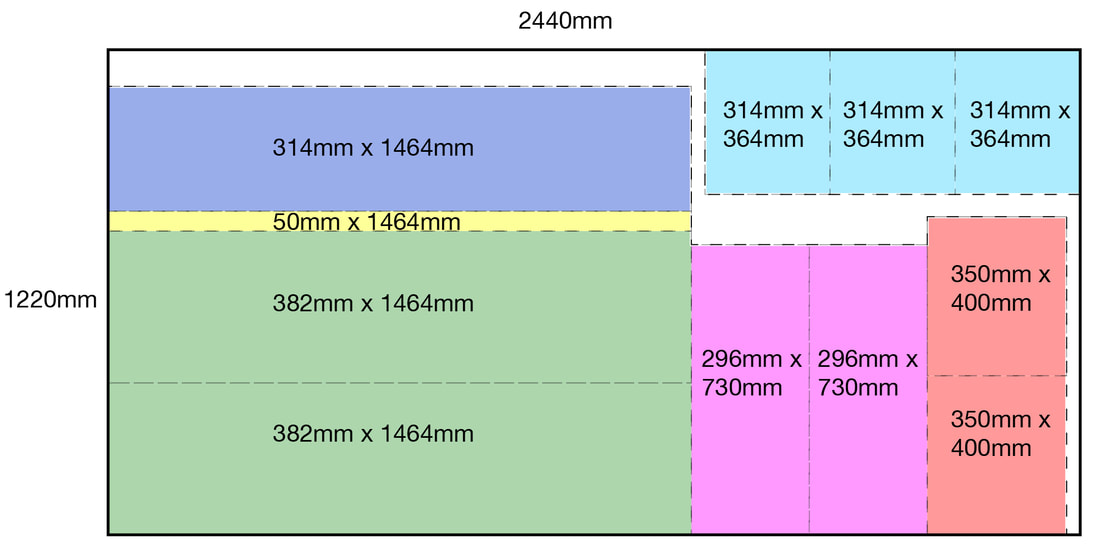

Good Luck! CREDIT: Image: Amanda Moore, SÖCIÅL SPÅCE Project 2020 When lockdown started in early 2020, in relation to the global pandemic, the arts were badly affected. In terms of galleries, many had been forced to temporarily close in towns due to social distancing measures. In the summer I was lucky to be commissioned by People United, along with 5 other artists, to design artistic concepts which would make social spaces kinder and, well, more social. This culminated in a graphic leaflet which people could download at home. The idea was for communities to work together to produce an outdoor artwork which would assist with social distancing in a playful way. The artworks would allow us to interact more with our local public realm, particularly at a time when indoor spaces were subject to tighter occupancy guidelines.

Through 2020 and beyond, could there be a greater impetus to take artwork outside onto the streets and what are the benefits?

And are there any limits to the placement of art outside of the gallery?

These projects are often commercially sponsored, paid for by arts councils and trusts or form part of planning application agreements or council regeneration projects. They can be temporary or permanent and they can have a much larger role than art as commodity. They are art as identity, interaction and engagement of people with their surroundings. CREDIT: Drawing: Amanda Moore When working as a freelance artist or creative, you need to be clear with your client about fees for your services and any other costs from the outset. You can also lose out on hard-earned fees because of simple invoicing mistakes. I definitely have. Here are some helpful tips: Decide whether you are charging an hourly/day rate, or flat feeIf the project is a service, like designing some graphics or editing photos as part of an ongoing freelance gig, you may wish to invoice on an hourly or daily rate. Make sure that you agree a rate in advance. It may be worth joining an artist membership site like a-n, (a-n.co.uk), for current recommended day rates. If your project is a one-off larger commission such as a piece of bespoke artwork, you may be better off agreeing a flat fee. Work out a budget breakdown to include estimated time you'll need for; project research, meetings, site visits and production using your day rate. Include an estimate of any necessary expenses and fabrication costs. Get quotations from any external fabricators. Day rate invoicingIf you are working on a day rate, include the time worked on the invoice and your hourly/daily rate so that there is no confusion over this. If extra work is required later, you can easily separate the extra work from the work already completed and invoiced for. Flat fee invoicingAgree a payment schedule if the work will run over a longer timeframe. This may be based on completion of certain tasks or on set dates along the way such as once per month over a six month project. This is very important. Otherwise you could end up working for a long time with no payment which will affect your cash flow. You may also end up invoicing periodically based on the amount of time you have spent and not end up receiving the full lump sum fee agreed once the project is complete. If you have to outlay a lot of money on materials, make sure that your payment schedule is timed and sufficient to cover these costs to reduce your risk. Scope of servicesMake sure to detail what you will be responsible for and what will be provided by others before starting any work. Who is printing the final artwork? Will you be expected to pay for any consultant costs such as engineering fees for a bespoke three-dimensional work? How many meetings will you be expected to attend? How many design revisions will you allow within the agreed fee? This all needs to be agreed or your fee could be spread very thinly. Delivery and installationFollowing on from the point above, make sure that you agree with your client who will be hanging or installing any physical work and whether you are expected to arrange delivery. Get quotations from specialist companies as there could be a massive cost difference between a small van delivery and a large truck with crane. ReceiptsKeep your expense receipts as proof of costs for clients if required. You will also need them in order to claim any tax back on your yearly income tax return. Basic invoice information to include:

Tax on incomeKeep copies of invoices in separate folders for each tax year with receipts. This will make completing your income tax return much easier. Register to pay tax in your country, (called Self-Assessment in the UK), and make sure to put the tax away in a separate account when you get paid so that you don't spend it! Don't forget that there may be other deductions such as student loan payments and National Insurance in the UK.

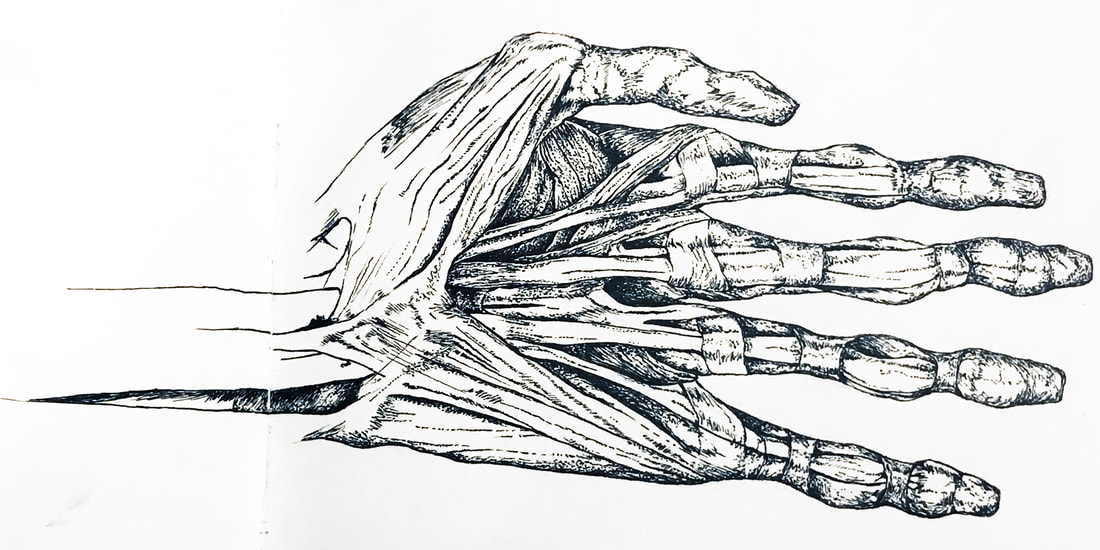

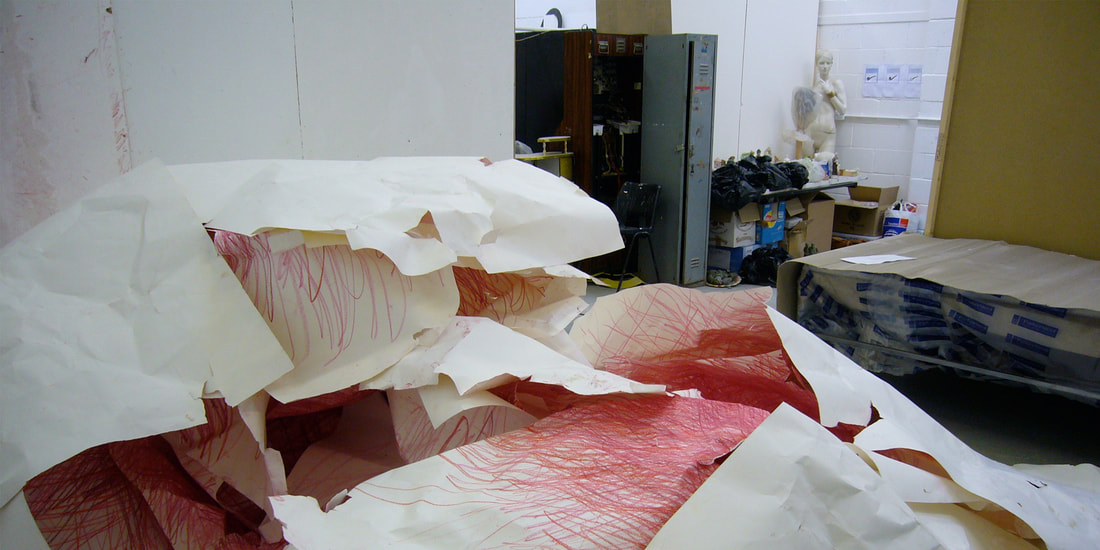

CREDIT: Photo (and mess): Amanda Moore You may be planning to join a visual arts programme as an undergrad with a broader base. Or you might be about to specialise as a grad student in painting, sculpture, film, print, illustration or photography. How do you make the most of this exciting opportunity? 1. Choose a school which has the right teaching style for youCourses vary widely. Some people will be happy to be shown to their studio space and left there for 2 weeks until the next tutorial. Others will prefer a more structured course. The school I attended had art history lectures, life and anatomical drawing classes and technical workshops which worked better for me when transitioning straight from high school/college. With less structured courses, you will likely have to be more proactive in reading, researching and visiting shows. Something inspirational has to go in for something creative to come out. 2. “Don’t borrow, steal”This was a great piece of advice given by a tutor. It will be tempting to try and emulate the style of an artist you like. The better approach is to understand what their work is about, what is the concept, and then own that, improve on it and make it yours. Start with the idea and the style will follow. 3. Make your art politicalYour art doesn’t have to be overtly about topical political issues but it’s easier to build up a portfolio of work if there is a central theme or reason for why you are making it and showing it to others. Art is also a great platform for expressing or critiquing something, even for critiquing art itself. So many ideas are communicated on social media platforms to people who already have similar views and so exhibiting art is an opportunity to bring ideas to a wider network. 4. Critique is not criticismCrit days can feel like a firing squad as you clear up your studio space and prepare to stand up and explain your work to tutors, visiting lecturers and your fellow students. A well-run crit should give objective feedback and help you to feel clearer in the direction your work is going. For better outcomes, choose elements of your practice which you feel you require feedback on and ask another student to take some notes for you as we all have a tendency to only remember the negative comments. 5. Market your artBe proactive and don’t rely solely on the final degree show for people to see your work. Tutors may not offer any guidance on this. You might use social media platforms to showcase your work whilst also giving more insight into your unique concepts and making techniques. Setting up a website will enable you to direct people to your work when you meet them. Set up your own show, or a themed group show, and be open-minded about venue locations with good footfall. Apply for commissions and competitions. 6. Grow your networkFollowing on from point 5., talk to people, lots of people. Talk to your studio colleagues about goals, share contacts, offer to help each other. If you meet someone and collect their card ‘old-skool’ or connect with them on social media, set up reminders to check in with them now and again. Share something of interest or find out whether you can help with something they are working on with no expectations in return. Not all opportunities will come your way by applying for them, many will be created and offered from within your network. 7. Take advantage of other school resourcesYour school may have a whole set of wider resources which you can use as part of your paid tuition. This may include specialist equipment, lectures in other subjects, business courses or even counselling. All of these resources would cost you some serious coin if you paid for them privately. 8. The art world can be a fickle placeIt will prove difficult to understand why curators and galleries prefer certain artworks and artists and some of your colleagues may be more sought after than you at the final degree show. Your art is not bad, there is a place or a situation for all art. It may not be this gallery but another one, it may be for publications, for public commissions, for private collectors, etc. 9. Find ways to make your practice affordable post-schoolIn school you may have access to everything from printmaking presses to welding equipment. However, you may or may not have easy or affordable access to these tools after school. Think about diversifying the materials you use so that you can keep creating without having to outlay a lot of money on equipment. Depending on your location, you can also rent workshop space on a daily basis. 10. You will always be an ArtistAs I approached graduation, I knew that I would need to take a day job and find a way to come back to producing my art in the future. If you want to, or have to, take a break from creating art full-time after graduation, don’t worry, you will always be an Artist. Firstly, make your art for yourself. You will also bring a way of seeing things into everything else you do and you may even become a different kind of creator - a writer, a musician, a marketer, a designer … be open to all opportunities. What are some of the most valuable things you have learned at art school?

CREDIT: Photo: Amanda Moore You’re off to architecture school, or maybe you’re already there. It’s going to be tough and challenging at times but also an opportunity to test your ideas and concepts without constraints. Before I started at architecture school I didn’t know any older students or qualified Architects to ask how they found the experience and the things they wish they’d known or done differently. Here are the top twelve things I personally wish I’d known before I started: 1. Architecture school is THE opportunity to push creative ideasThis is your chance to explore all kinds of concepts; how you think cities should work, whether food production should be an integral part of our homes, sculptural forms, … You won’t have the constraints of a ‘real’ client and a brief, likely because you’ve also created your own client and brief. I didn’t fully appreciate this until I was asked to draw 53 bathroom packages for a housing scheme in my first real job. At architecture school I often viewed crits and deadlines as something to survive rather than as a chance to push my ideas to their full potential. My best work happened when I found the bravery to stop, review and start over, even days before a presentation. 2. You will have to work very hardTutors will demand a lot in terms of both quality and quantity. You may be sitting in a tutorial and hear, "just do a larger ground floor plan … and erm, a couple more sections … and some night time renders … and an exploded axonometric… and maybe your building should be more like this…" (tutor turns model upside down). There’s no way around this. However, when it comes to entering the workplace, you’ll have gained phenomenal skills in meeting deadlines even when working a 9 - 5 (ish), rather than a 7 - look, the sun’s coming up again. 3. There are MANY different types of ArchitectAt architecture school you may feel envious of that person who can do beautiful hand drawings, or the person who has amazing graphics in their portfolio. The actual job of being an Architect is many different things and there are roles for all kinds of Architects. A good boss will recognise this. Being able to solve technical problems creatively, being organised, being able to deal well with clients and contractors with the diplomatic skills of a hostage negotiator … Do not hang your future success as an architect on how many people drool over your portfolio in school. 4. Learn as many different types of CAD software as you canHand drawings are beautiful but time-consuming. If you can master 3D software, you can take multiple plan and section cuts, experiment with line weights and layering of colour, shadow and photo images to create equally beautiful drawings with a sense of depth. You’ll need architectural software skills in the workplace. Learn as many as you can; Autodesk, Rhino, Vectorworks, Archicad, Revit, Adobe Photoshop, Illustrator, Indesign, etc … 5. Learn about sustainable methods of buildingWe have a crisis on our hands. In terms of construction, we need to make our buildings more energy efficient in order to reduce ‘in-use carbon’ and also less carbon-intensive in their materials to reduce ‘embodied carbon’. A good understanding of this can be taken with you into your future job where you will explore how to implement sustainable technologies in client projects. We need to encourage clients to go way above the minimum requirements of regulations where possible. Hopefully, the results of more ambitious clients and projects will trickle across into all sectors of the built environment. 6. You will find many egomaniacsAt architecture school the best resource is your colleagues. People who will help critique your work late in the studio, swap photoshop techniques and tell you when there’s a discount on foam board. You will be lucky enough to meet many of these people. However, you’ll also meet others who will see sharing as something which will cause them to lose something. I recall a student colleague who would work with a blanket over his head and his MacBook, yes, a blanket. He didn’t want any of us to steal his genius ideas but he also missed the point of working in a shared studio. Wonder how the blanket’s working for him in the workplace … Maybe he should invest in one of these. CREDIT: Photo: Becky Stern 7. Make modelsArchitecture is a three-dimensional experience. Make models to fully explore your ideas. Speed modelling is a great way to try out ideas quickly. Cardboard, wire, clay, wood … whatever is easily available. You can get a lot of use out of these. Light them and photograph them from different angles, print photos and draw over them, add people in poses which interact with your forms. 8. Spending more money on architectural materials doesn’t make a better projectI was part of a studio unit which specialised in digital design. This involved a lot of 3D printing which was incredibly expensive. I wanted to make a large 3D concept model based on beehive structures with lots of little cells. I found that I could use masking tape and roll it back on itself to make thousands of tiny tubes which also stuck together to build forms. During the crit, my tutors asked where I got this "amazing" yellow material from. I’m not going to lie, it took longer than 3D printing but the forms were much finer and I could review and alter it as I was going. There are always inexpensive options. 9. Portfolio printing is expensivePrinting at a shop will prove pricey and the queue at the school printers before crit day will have you crying. Think about investing in your own large-format printer, perhaps going in with a few other people, and then reselling it at the end. Remember, for general portfolio sheets, you may be able to use a smaller format printer. You are only restricted by the width of the paper feed and can go as long in paper length as you like. 10. Always get your drawing scales correctOne of the things which will greatly annoy a tutor or your boss is showing drawings at the wrong scale, or no scale. Also, don’t use that classic well-known scale of 1:345 or multiple scales on the same drawing. The number of crits you will attend where someone is being chastised as the toilets are designed for a giant and you’d have to walk sideways through a door. It’s an unnecessary distraction from your good design concepts. 11. Keep a digital backup of your workScan your drawings and photograph your models. Keep a backup of your portfolio on the cloud. Things can get lost. It’s useful anyway so that you can send potential employers images of your work or print a smaller portfolio book for interviews. I had an unfortunate situation where my portfolio and model went missing from an examination room. Luckily I had the portfolio saved electronically but I hadn’t photographed the model. 12. Think about choosing a different Architecture school to complete your studiesWhat I learned from my colleagues working in architecture practice and tutoring at architecture schools is that different schools have different styles of teaching. I stayed at the same school for my whole architectural education but it would have been interesting to have experienced different schools. Another way around this is to be part of different design units/studios at the same school. In my final year, I joined a computational unit which was very different to all of my previous study years. I brought a (small) bunch of parametric software design skills with me to the workplace and started a design workgroup which helped project teams to model complex forms more efficiently. Do you have any things you wish you'd known or have just discovered about studying Architecture...?

CREDIT: Photo: Amanda Moore Have you ever felt as though you are a writer who isn’t writing, a dancer who isn’t dancing, an artist who isn’t making art? What can you do with that liberal arts degree? Maybe there are alternative ways to get back into it. Becoming an ArtistIf there was one thing which defined the start of my career of being an artist, it was the uneasiness in feeling justified in calling myself an “artist”. Being a student is one thing, and studying at art school, the luxury of spending all day in your allocated studio space, you look like an “artist”. But fast-forward to the End of Year Show and this seminal event separates the “artists” from the people thinking, ‘but that guy only came in for a few hours and stood outside smoking roll-ups and then dragged some stuff out of a skip, now he’s got work in the Saatchi collection’. If you’re not going to have a collector buy all of your work and then have a career creating, exhibiting and selling stuff from your studio, (which used to be a set of garages in East London), then what’s the point of all this? It’s a bit of a throwback but reminds me of the film Frances Ha back in 2012, about a 27 year-old apprentice for a dance company who isn’t really a "dancer". She receives the standard dinner party question, ‘so what do you do?’ and handles it earnestly; CREDIT: Photo: Pine District, LLC Andy: So what do you do? Frances: Eh... It's kinda hard to explain. Andy: Because what you do is complicated? Frances: Eh... Because I don't really do it. Make or Break, The End of Year ShowWhen I studied at the Royal College of Art, I remember standing near my work at the End of Year Show which was being completely panned by a critic who taught there. I was caught between being embarrassed and wanting to get as far away from that work as possible, but also wanting to run up and slap him across the face. He then turned around with a middle-class ‘Darling’, and told me how great the work was. Two-faced jerk. Quite a few of my colleagues sold work as disparate as clay figures of animals, ‘skip-man’s’ up-cycled objects from the trash, and some really nice intricate and skilfully crafted objects somehow made from dust. I was happy for them. Not really. I couldn’t figure out what made one person’s art “art” and made one artist an “artist”. Nothing was common amongst the work bought by collectors. It wasn’t the types of material used, it wasn’t the subject matter, it didn’t seem to be based on a particular trend. What somehow felt more strange was that curators I knew who were at the show kept offering me jobs. Jobs to help them do research for books, to help run studios for other artists, to tutor their A-Level kids, (that’s age 16-18 in the UK). Frankly, I was offended. Much like Frances was when she tried to get a spot ballet dancing in one of her company’s shows and the Head of School offers her a job in the office. I mean, how dare they offer me way above the median UK wage to manage a studio, or four times the amount a care assistant earns to drink coffee and watch a 16 year-old do their homework? To 'Art' or not to 'Art'So what did I do? I had a choice between going for it, potentially living in some kind of squat or squalor in order to afford a studio space with the financial situation at the time and keep trying to somehow break into the elusive “art scene”, or taking one of the day jobs. Or maybe half a day job and half of the squalor. How did I decide? I had to decide what my priorities were. I felt pressured to be an exhibiting artist with London-based shows, (shows in established galleries), especially following the gift of being able to study at the RCA. One of my tutors gave me some good advice, that you can keep coming in and out of things through your life. He said not to worry about it, ‘you’ll always be an artist’. If I was honest, I wanted what the baby-boomers had - a regular income, a working vehicle, a home. So I took the day job, all of the day jobs - tutoring, managing studios, helping curators and learning more about the business of the art world. It took me several years to even understand what my work should be about or what it could contribute. Subsequently, I studied architecture as I liked the idea of designing things which would serve society, rather than potentially become commodities, and I started to get into working on large-scale public sculpture commissions. This was finally a way for me to combine everything I was interested in - sculpture, making things which have a definite community benefit, and getting paid. Having a brief, a need, was much more helpful to me than when I was in the studio all day trying to find a need for my work. And public commissions often involve a whole collaborative team of interesting people including clients, the local community, engineers, planners and fabricators.

Frances also took the day job, and then she got into choreographing her own dance in her own style. It wasn’t her original plan but she got to be a stronger contributor to the industry she loves. |

AuthorWhat am I doing here? I'm collecting sea water to fill 1,000 bottles and hang them from a scaffold inside an old ruin. Why? Why not? Archives

December 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed